Natural gas production has been booming in southwestern Pennsylvania, but it may also yield multiple health complaints, especially for residents surrounded by oil and gas facilities.

Sore throat, burning eyes, headaches—these are just a few of the health problems reported by people living near oil and gas operations in southwestern Pennsylvania, according to a new study.

In the study, researchers estimated residents’ exposure to oil and gas emissions and used a novel method to assess potential health consequences related to their exposure level. The study does not prove cause and effect but showed that people surrounded by higher numbers of wells were more likely to suffer a greater number of symptoms.

“We need to ask questions about what are in those emissions and what is it about more wells that could create that link to health symptoms,” said study coauthor Hannah Blinn, a former graduate student at Chatham University. “We really need to look at how more and more wells in an area could affect a community.”

The study was published in PLOS ONE in August.

Boom or Bust for Pennsylvania Residents?

Pennsylvania has experienced a boom in natural gas production, thanks to widespread hydraulic fracturing—more commonly known as fracking—of the underlying Marcellus Shale. The practice took off in Pennsylvania around 2005, and now there are more than 7,700 active wells. In 2017, the state accounted for about 19{464181316c28bea4db76e6a38127b032d62ba553e1a210ad2f4f889997fffc93} of the U.S. natural gas market, second only to Texas in production.Toxicologists have struggled to point to specific exposure levels that are unsafe, and the industry remains poorly regulated.While the industry provides many jobs, a growing body of research suggests that exposure to emissions from shale gas development is associated with a host of health issues, including respiratory and neurological problems and higher rates of hospital use. But toxicologists have struggled to point to specific exposure levels that are unsafe, and the industry remains poorly regulated. In Pennsylvania, well pads can sit 500 feet from a home or a school—with no limit on the number of wells in an area—and companies report their emissions just once per year.

Blinn wanted to find the best way to evaluate health effects from shale gas emissions, so she teamed up with researchers at the Southwest Pennsylvania Environmental Health Project (EHP). The nonprofit, which aims to protect public health from oil and gas development, had performed more than 100 health assessments on Pennsylvania residents with symptoms related to nearby emissions.

Estimating Exposures

Blinn used three different modeling methods to estimate the exposure levels experienced by the residents. Each method showed a significant relationship between exposure level and the number of symptoms reported by the participants, but cumulative well density, which is the number of wells in a given area, was the most effective method.The analysis showed that muscle aches; problems affecting the eyes, ears, nose, and throat; and neurological issues, such as trouble concentrating, were commonly reported by people living in areas with large numbers of wells. To identify symptoms that were more likely to pop up with greater exposure, the researchers borrowed an analytical tool from ecologists, the threshold indicator taxa analysis (TITAN). Traditionally, this analysis helps interpret species diversity across an environmental gradient—for example, understanding which plant species might leave or colonize a field with increasing amounts of fertilizer runoff. TITAN showed that muscle aches; problems affecting the eyes, ears, nose, and throat; and neurological issues, such as trouble concentrating, were commonly reported by people living in areas with large numbers of wells.

The study included only adults, although children were present in some of the homes. “One of the big worries that I have as a toxicologist is that we’ve restricted ourselves to health effects from people who could tell us what they were—adults,” said coauthor David Brown, an environmental public health scientist at EHP. “If we see an adult showing health effects, then we should be concerned about children.”

Brown is right to be concerned. “We have observed [a] higher likelihood of children with leukemia and congenital heart defects being born in the densest areas of oil and gas development,” said Lisa McKenzie, a public health researcher at the University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus who has studied the potential impacts on children in Colorado.

Getting to the Source

To further this research, air sampling at the individuals’ homes should be the next step, said Blinn, because their exposure estimates were based on modeling, not on chemical analyses. While expensive, air sampling could show more direct relationships between symptoms and exposure levels on specific days and help the researchers drill down on which chemicals are related to which complaints.

Michael McCawley, an environmental health scientist at West Virginia University who was not involved in the study, said that the work is an interesting and valuable contribution but agreed on the need for more air sampling. While modeling exposure is a common practice, he pointed out that a lot of assumptions factor in to the models. “But what they have discovered is, where there are wells, there’s disease,” he said. “The question is, How does the pollution get generated, and how does it get from where it’s generated to where it’s doing the damage?” In a previous paper, McCawley proposed that the cause of these symptoms may be not activities on the well pads but the ultrafine particles generated by diesel trucks as they make thousands of trips to and from the sites.

The findings from this and other studies bring up questions about the future growth of the industry. “If things like density and more emissions are related to health symptoms in our paper and other papers, we need to think about how many [wells are] too many,” said Blinn.

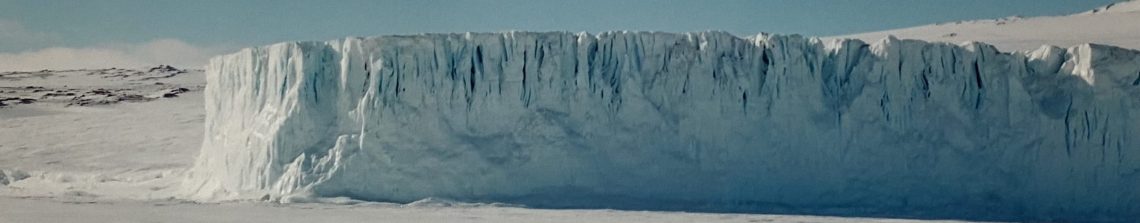

Top photo by Bob Donnan